Investors are less optimistic about the Korea Corporate Value-up program:

- Opinion polls predict a loss of seats for the ruling party. This would either lead to more gridlock in parliament or even an outright majority by the opposition, potentially making it harder to push corporate reform-related measures (tax breaks etc.) through parliament.

- The National Pension Service voted against demands by a group of activist shareholders for a Korean chaebol member to pay higher dividends. The reason given was that the demands were “excessive”. This was a disappointment to some, as just prior to that the NPS had expressed positive sentiments towards the corporate reform programme, which incorporates measures to encourage higher payouts.

There has been some positive news as well. The Financial Supervisory Service brought forward its release of the draft “Corporate Value-Up” guidelines to April. It announced a revision of the stewardship code to support investors calling for companies to implement Value-Up reforms. The Finance Minister outlined plans to ease the tax burden for companies that actually do so. We also saw an example of successful activism by retail investors as they were able to block a potentially value-destroying merger between a chemicals company and a pharmaceuticals producer.

Nevertheless, the overall tone is negative and it caused some quite extreme price reactions among the potential reform beneficiary stocks.

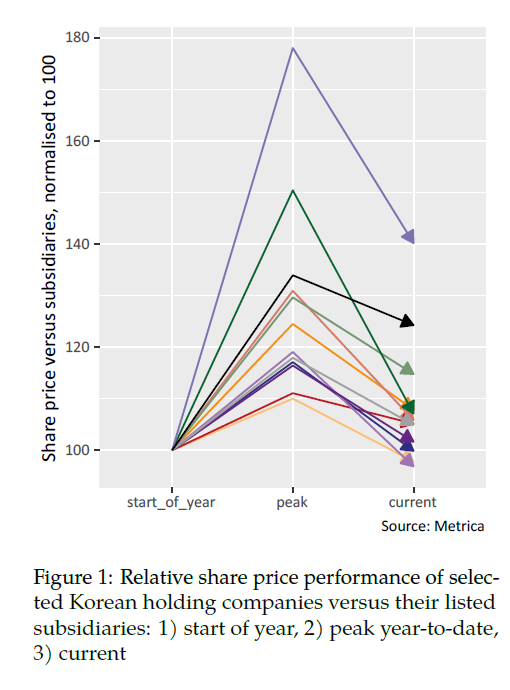

The chart below shows how the share prices of one such group – listed holding companies – have reacted. It shows the start of the year level, the peak year-to-date level and the end-of March level for twelve representative holding companies, normalised to 100 and expressed in terms of performance relative to listed subsidiaries. Upward movement represents a reduction in the NAV discount of the holding company, and therefore can be said to indicate the market’s estimate of the probability of corporate value enhancement at the holding company level.

Following President Yoon’s speech in January, the twelve companies initially rallied against their listed subsidiaries by between 10% and 78%, as shown in the chart. Then, as disappointment set in, these moves were retraced in the middle and end of March. In the mildest case, the retracement was 29% of the initial move, and in the most extreme cases, it was more than 100% (i.e. the arrows end up below the starting point). In other words, several names are now trading cheaper than they were at the start of the year before the talk of reform got underway. This has thrown up some compelling opportunities and it may also be an example of how markets with a high proportion of retail investor flows such as Korea are prone to overshooting on the downside as well as the upside – to us, it doesn’t make any sense that the implied probability of reform should be lower than it was at the start of the year.

As we wrote previously, once the guidelines have been published, it will be hard for companies to stick their heads in the sand to avoid awkward questions from shareholders. The number of activist managers in Korea continues to increase, and we can expect to see frequent references to the guidelines in public campaigns.

Also, although the election results may present a temporary setback for the programme, many aspects of Corporate Value-Up can still be implemented without changing the law. The example of Japan shows how non-legislative measures such as changes to stock exchange listing rules can have a significant impact.