We looked at the Factset SharkWatch database, which tracks global activism campaigns for the last ten years. The dataset initially covered only US campaigns but in recent years has improved its non-US coverage to the extent that we believe it now provides meaningful statistics for Asia-Pacific.

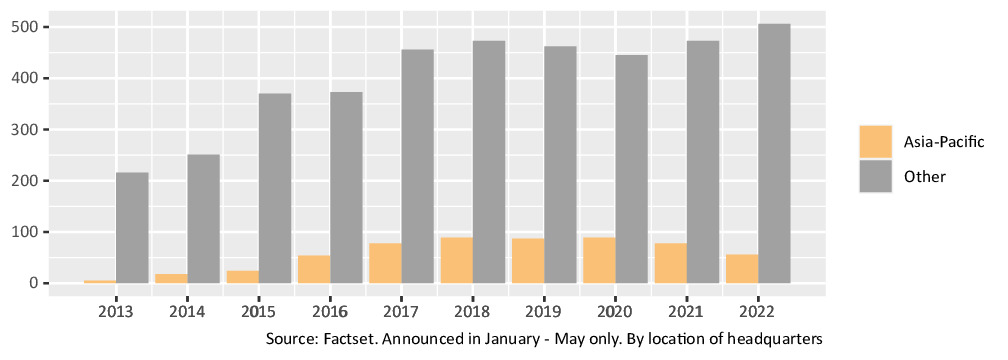

The primary observation is that, while global activism has already started to rebound from the depths of the pandemic – rising 5.2% since 2020 – this growth has all been driven by campaigns outside Asia-Pacific. Figure 1 shows how Asia-Pacific activism (which accounts for around 17% of the total) is still down by 37% compared to 2020, even as the rest of the world has risen 13.7% (note that we considered only campaigns announced in January to May of each year, to make the results comparable across years).

Figure 1: Activist campaigns by region

Why the divergence? We believe it is simply explained by the fact that the three countries which account for 91.1% of the “rest of the world” dataset – namely the USA, Canada and the UK – have all been rolling back Covid restrictions faster than most countries in Asia-Pacific. This has made activism easier to execute and more effective in these markets.

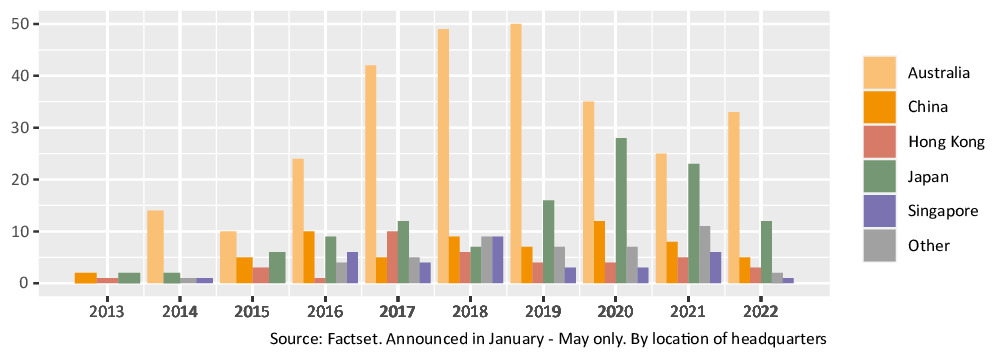

Figure 2: Asia-Pacific activist campaigns by region

Within Asia-Pacific, we see a similar trend. Activism targeting Australia-headquartered companies, which typically accounts for around half the regional total, has been rebounding in 2022 (figure 2), in line with Australia’s re-opening of its economy. Conversely, countries such as Japan and China which persist with closed border policies are still seeing activism falling year-on-year.

Looking forward, with the worst of the Covid restrictions seemingly over, we believe that Asia- Pacific as a whole should soon follow the rest of the world in seeing a resumption in activist campaigns.

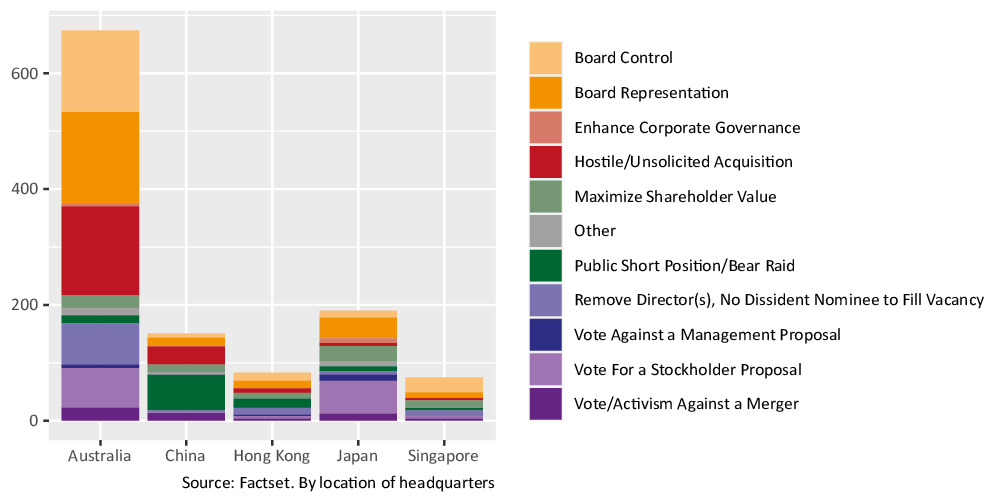

It is also interesting to note how the objectives of activist campaigns vary widely depending on the market (figure 3). For example, in Australia, campaigns have a wide variety of objectives, and in particular, the proportion of activism relating to hostile and unsolicited acquisitions is the highest in the region.

Figure 3: Asia-Pacific activist campaign objectives

However, activism directed at mainland Chinese companies is mostly in the form of “bear raids”, i.e. where investors take short positions in stocks and distribute negative research aimed at driving prices down.

Most of these companies are listed outside their home market, where such activism would not be realistic. The high weighting of bear raids illustrates how other types of activism – proxy fights, hostile acquisitions, shareholder proposals – are rare among Chinese companies due in our view to high insider ownership and a relatively underdeveloped corporate governance infrastructure.

Japan on the other hand has a high weighting of “shareholder proposal”-type activism, reflecting the relative ease with which such proposals can be incorporated into shareholder general meeting agendas in Japan, as well as the growth of activism-oriented funds in that country.